Airspace confuses new pilots more than almost any other topic. The letters and numbers seem arbitrary, the rules inconsistent, and the consequences of errors severe. But the airspace system follows logical principles, and once understood, navigation through any class becomes routine.

The Airspace System Philosophy

Airspace classifications exist to separate aircraft operating under different rules at different speeds. The system protects everyone—fast jets descending to major airports, slow trainers practicing near small fields, skydivers, gliders, and helicopters all share the sky. Classifications create order from potential chaos.

Controlled vs. Uncontrolled

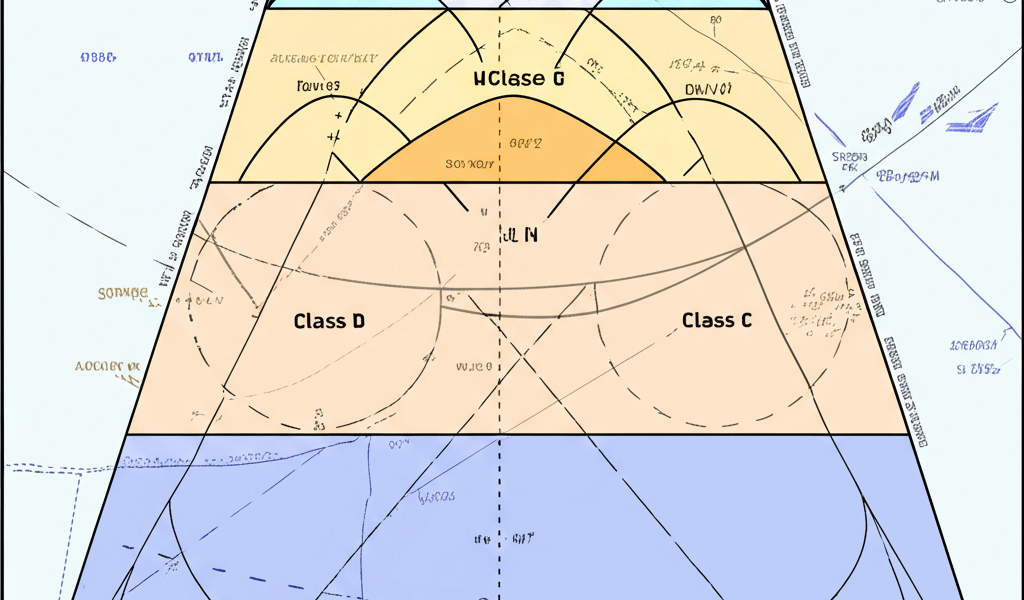

The fundamental division is controlled versus uncontrolled airspace. In controlled airspace (Class A, B, C, D, and E), ATC provides services and may issue instructions pilots must follow. In uncontrolled airspace (Class G), pilots are responsible for their own separation with no ATC services available.

Class A Airspace

Class A exists from 18,000 feet MSL to Flight Level 600 (approximately 60,000 feet). All operations in Class A require instrument flight rules—no VFR permitted. This simplifies ATC’s job at high altitude where all aircraft are under positive control.

Entry Requirements

Instrument rating, instrument-equipped aircraft, IFR flight plan, and ATC clearance. Most private pilots never operate in Class A unless they pursue instrument rating and high-performance aircraft.

Class B Airspace

Class B surrounds the nation’s busiest airports—major hubs like Denver, Atlanta, and Los Angeles. The airspace looks like an upside-down wedding cake, with layers expanding outward as altitude increases. The surface layer is smallest; higher layers extend farther from the airport.

Entry Requirements

To enter Class B, you must receive explicit ATC clearance. “Cessna 3AB, cleared into the Class Bravo” means you can enter. “Cessna 3AB, remain outside the Class Bravo” means you can’t, regardless of how close you are or what services you’re receiving.

Pilot and Equipment Requirements

Pilots must hold at least a private pilot certificate (or student with specific endorsement). Aircraft must have two-way radio, Mode C transponder, and ADS-B Out. Some Class B airports have specific operating rules covering landing/takeoff minimums.

Weather Minimums

Class B requires 3 statute miles visibility and clear of clouds—the same as other controlled airspace near airports.

Class C Airspace

Class C surrounds airports with moderate traffic volume—busy enough to warrant radar service but not as intense as Class B. Typical configuration is a surface area 5 nautical miles in radius, and an outer area extending to 10 nautical miles from the surface to 4,000 feet AGL.

Entry Requirements

Two-way communication must be established before entry. Unlike Class B, you don’t need explicit “cleared into” language—if the controller uses your callsign, you’re authorized to enter. “Cessna 3AB, standby” establishes communication; “Aircraft calling, standby” does not.

Pilot and Equipment Requirements

Mode C transponder and ADS-B Out required. No specific pilot certificate requirement beyond basic pilot privileges.

Services

Class C provides sequencing of VFR arrivals and separation from IFR traffic. You’ll receive vectors and instructions but retain responsibility for cloud clearance and terrain avoidance.

Class D Airspace

Class D exists at airports with operating control towers but lower traffic volume than Class C. The airspace typically extends from the surface to 2,500 feet AGL within approximately 4 nautical miles of the airport.

Entry Requirements

Same as Class C—two-way communication established before entry. If the controller responds with your callsign, you may enter.

Equipment Requirements

Two-way radio only—no transponder or ADS-B specifically required for Class D (though they’re required in many overlying Class E areas and for operations above 10,000 feet MSL).

Part-Time Operations

When the tower is closed, Class D reverts to Class E or G depending on the specific airport. Check the Chart Supplement for the operating hours and reversion classification of specific airports.

Class E Airspace

Class E is controlled airspace that doesn’t fit the other categories. It exists in many configurations, serving as the “default” controlled airspace where ATC services are available but specific terminal requirements don’t apply.

Surface Areas

Some airports have Class E surface areas—these extend from the surface, usually 700 or 1,200 feet AGL, and are designated when a control tower isn’t present but instrument approaches exist.

Transition Areas

Class E often begins at 700 or 1,200 feet AGL to provide controlled airspace for instrument approaches and departures. The magenta faded line on sectionals indicates Class E beginning at 700 feet; the blue faded line indicates 1,200 feet.

General Class E

Above 14,500 feet MSL, Class E exists everywhere except over specific military operating areas. This provides controlled airspace for en route IFR traffic.

Weather Minimums

Below 10,000 feet MSL: 3 miles visibility, 500 feet below, 1,000 feet above, 2,000 feet horizontal from clouds. Above 10,000 feet MSL: 5 miles visibility, 1,000 feet below, 1,000 feet above, 1 mile horizontal from clouds.

Class G Airspace

Class G is uncontrolled airspace—no ATC services are provided, and no clearance or communication is required. It exists where Class E doesn’t reach the surface.

Typical Configuration

Away from airports, Class G extends from the surface to 700 or 1,200 feet AGL, above which Class E begins. In remote areas without instrument approaches nearby, Class G may extend to 14,500 feet MSL.

Weather Minimums

Day VFR below 1,200 feet AGL: 1 mile visibility, clear of clouds. Night VFR below 1,200 feet AGL: 3 miles visibility, 500 below, 1,000 above, 2,000 horizontal from clouds. These reduced minimums reflect the lower traffic density and pilot responsibility in uncontrolled airspace.

Practical Navigation Tips

Modern avionics display airspace boundaries, making identification easier than paper chart reading. But understanding remains essential—you need to know the requirements before entering, not just the location.

Preflight Planning

During flight planning, identify all airspace along your route. Note entry requirements, frequencies, and weather minimums. Prepare the radio calls you’ll need.

In-Flight Awareness

Monitor your position relative to airspace boundaries. When approaching Class B, C, or D, make contact early enough to receive clearance or establish communication before entry. When in doubt, remain clear until you’ve confirmed entry is authorized.

When Confused

If uncertain about airspace status or requirements, ask. “Denver Approach, Cessna 3AB, confirm I’m clear of the Class Bravo.” Controllers would rather answer a question than deal with an airspace violation.

Learning the System

Airspace understanding comes from study and practice. Use training flights to transit different airspace types. Practice the communications. Experience the differences between busy Class B environments and uncontrolled Class G airports.

The system makes sense once you understand its purpose: keeping differently-equipped aircraft separated while allowing maximum access to the national airspace. Learn the rules, respect the boundaries, and you can fly anywhere the airspace system permits.